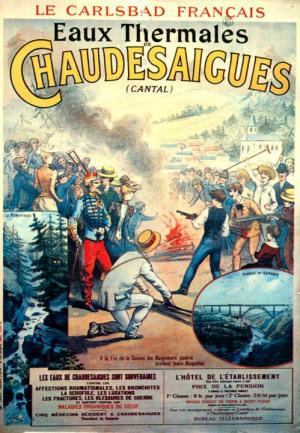

At first I came on a little strong. It was a time when, like many, I thought all you needed was a big piece of equipment to take beautiful photos.

The end of the 80s was still a time of analog photography, which meant much more than investing in a simple camera. It was at this point that finally saw the light.

I felt sure it was light that needed to be mastered, and put to work in the service of my passion. I wanted to photograph my tattoos.

You can imagine how frustrating it was to spend long hours creating a tattoo, just to see it walk out with its owner when the session was finished.

And I won’t even mention the disappointment I felt after developing the first films. If it had been a success, this film should have served as a record of my “masterpieces”.

I would also rather not describe the catastrophic results given by a flash on a fresh tattoo, or the fact that I was so disappointed by my first attempts that, more than once, I wondered if someone was sabotaging the development of my photos.

Trying to understand shutter speed, apertures, different types of film sensitivity and depth of field made me feel dizzy.

The evening I played around with the camera, my field of vision was occupied by tattoos, giving me the chance to look at each little accessory and piece of equipment from a new angle.

We could of course go a lot further, finding ourselves in an abstract universe that would open up a world different the one we think we perceive.

Is it not incredible to observe the same scene and not see the same thing?

It can sometimes simply change our point of view, our scale and the distance that separates us from situations, objects and even the people around us.

It makes a lot harder to assert oneself when we are unable to take into account the subjectivity of ourselves and others.

And it makes it a lot harder to tell ourselves we are right.